Popular Articles

Running and OsteoarthritisIn This Article

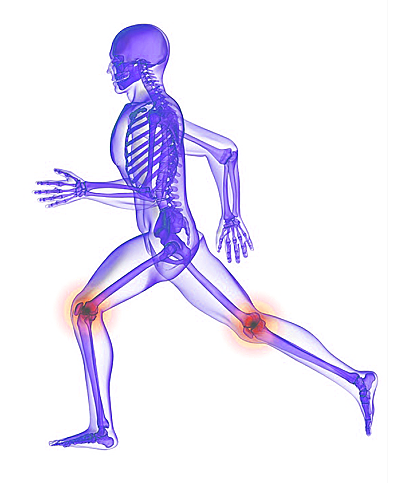

Because running involves repeated impacts on the joints, regular runners fear that this form of exercise may increase their risk of developing osteoarthritis. Is their fear real?

What is Osteoarthritis?Osteoarthritis is a form of arthritis and a degenerative joint disease. The parts of the joint most degraded in osteoarthritis patients are the subchondral bone and articular cartilage. This degradation leads to the stiffening of the joint as well as pain, tenderness, and restricted range of limb articulation and movement. Root Causes of OsteoarthritisThere are different causes of osteoarthritis and these can be traced to genetic, developmental, metabolic and mechanical causes.

Developmental causes of osteoarthritis refer to the improper formation of bones and joints during the formative years of life. This incomplete or improper development of the joints may not cause disability at all. However, because the joints are weakened, they are very likely to degrade rapidly. Metabolic causes refer to all causes involving drugs, diets and endogenous chemicals including the cells of the immune system. Sometimes, the products of metabolic processes may damage the protective membrane around the joint and then slowly weaken the cartilage. Mechanical causes of osteoarthritis refer to the daily wear and tear. This is the reason osteoarthritis occurs and worsens during old age. However, mechanical causes can also refer to high-impact wear on the joints caused by injury and strenuous exercises. These causes of osteoarthritis can start and accelerate the loss of cartilage in the joint between bones. As the cartilage wears off, the exposed bones rub against each other and are damaged. Then the synovial fluid lubricating the joint leaks out and contributes to the local swelling that is seen as effusion and tenderness of the skin over the joint. All of these damages cause the ligament to lose its ability to hold bones to cartilage. It also reduces degree of movement which can cause the muscles around the joint to atrophy. Osteoarthritis is the leading cause of disability in most countries. Osteoarthritis Treatment

In severe cases, corticosteroids and immunotherapeutic drugs may be recommended. Where these treatment options fail, joint replacement is the only treatment left to provide relief from chronic pain. What Studies Say About Running and ArthritisRegular exercise is now a widely recommended intervention for improving and maintaining good health especially as the average citizen gains more weight. Running is one form of exercise that is popularly used to improve cardiovascular health, reduce blood pressure and help burn calories. However, the impact of running on the body, but especially the joints, is a concern for runners especially as they grow older. Therefore, researchers have done a number of studies to access the effect of running on the development of osteoarthritis. Two Long-term StudiesIn a 1993 study published in The Journal of Rheumatology, seven researchers did a longitudinal study to determine whether running and aging increases the risk of osteoarthritis. The study involved 35 runners and 38 non-runners with the mean age of 63 years. All of them were already diagnosed with osteoarthritis of the knees, hand and lumbar spine. Between 1983 and 1989, the study participants were given different rheumatologic examinations ranging from questionnaires to radiographs. With more than five-year worth of data, the researchers were able to track the progression of the patients’ arthritis. The result showed that while aging increases the risks of osteoarthritis running did not accelerate the progression of osteoarthritis of the knees. A similar study was begun around the time of this first study. However, this second study spanned a longer period of time (almost 20 years) and studied the effect of running on the progression of osteoarthritis of the knee in long-distance runners. In 1984, the researchers recruited 45 long-distance runners and 53 controls. The mean age of both groups was 58 years. Over the course of 18 years, these study participants were given knee radiographs. The results of the study published in American Journal of Preventative Medicine in 2008 concluded that long-distance running among healthy elderly runners did not accelerate osteoarthritis of the knee. This conclusion means that severe arthritis is no more common among runners than non-runners and that the progression of arthritis is mostly determined by other factors including age and hereditary. What the Conclusions Mean?Other studies agreed that normal to moderate runners do not have higher risks of osteoarthritis than non-runners. However, athletes and long-distance runners may have a slightly increased risk of osteoarthritis. Even then the small increase in risk may be due to the proportion of athletes and runners who are genetically predisposed to osteoarthritis. These findings are consistent with mechanical models. Since impact loads during repeated and strenuous exercises can cause injury to the cartilage, it follows that high-volume runners and athletes are more likely to wear down the cartilages of their joints. However, some degree of exercise, including moderate running, is required to help strengthen the muscles as well as give flexibility to the joints. Therefore, running can actually improve the cartilage and joint functioning. Limitations of these StudiesContrary to the conclusions of most studies examining the impact of running on osteoarthritis, running may have a more significant effect on the development and progression of osteoarthritis. These studies do have their limitations and their designs can introduce bias into the results and conclusions. For example, most of the studies investigating the link between running and osteoarthritis concentrate on the effect of running on osteoarthritis of the hips and knees. However, running is just as likely to affect the lumbar spine and even likelier to affect the ankles. Osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine and ankles do affect runners just as much as osteoarthritis of the hips and knees. In fact, some will argue that the ankles do take most of the brunt of the impact of running. Secondly, most of these studies use elderly non-runners as controls against elderly runners and then conclude that the severities of osteoarthritis in both groups are similar. It may well be that elderly non-runners were put off running because the activity accelerated their osteoarthritis early in life. Therefore, elderly non-runners do not make an ideal control group. However, there is no better control group. Furthermore, these studies do not fully exhaust the major factors that can contribute to the outcomes of their results. For example, runners are not a homogenous group and running is not an activity performed with the same efficiency for everyone. Factors that can determine how much running affects the progression of osteoarthritis include running gait, running surface, types of running shoes, inclusion of other athletic activities with running and other biomechanical defects that can contribute to the impact of running on the joints. Lastly, very few studies investigate the long-term effect of running on people with painful arthritic joints. Most arthritis patients do experience pain while running and move away to exercises involving lower impact on the joints. Therefore, it is clear to see how it will be difficult to recruit participants for a study in which people with chronic or severe arthritis pain may have to repeatedly run. How to Exercise With OsteoarthritisPeople with mild to moderate osteoarthritis may choose to modify their running habit in order to reduce the effect of running on their joints.

Softer running surfaces transfer less energy and are less jarring to the joints than harder surfaces. For example, most people run on concrete and asphalt but concrete produces ten times the impact of asphalt. Hardness is however not the only determinant of the impact of a running surface. A running surface that does not permit a smooth rolling of the feet is just as bad as a hard surface. The effort it takes to land on and pull away from such surfaces reduces the efficiency of the runner’s motion, throws off his stride and tasks the joints and muscles more. This is why sand and snow are bad running surfaces.

To reduce the impact of running on the joints, arthritis patients are advised to start off their runs with exercises that strengthen the leg muscles. Such exercises include leg pumps, leg lifts, lunges, curls, stretches and squats. By strengthening the muscles of the calf and thigh, they can absorb more of the energy transmitted up the legs upon impact during running. Where arthritis pain prevents running on hard surfaces, runners can take to walking and running on treadmills. Besides treadmills, arthritis patients can also use elliptical trainers and stationary bicycles to exercise. Other forms of exercise that can improve fitness and match the cardiovascular benefits of running include bicycling, weightlifting and swimming including water walking or running. Some experts also recommend pilates, tai chi and yoga to gain back flexibility in the joints and help reduce arthritis pain. Final RecommendationsLow- and moderate-volume running does not increase the risk of osteoporosis and regular moderate running can actually improve the flexibility and strength of muscles and cartilages which will prevent osteoporosis. However, while running, it is good to choose the appropriate running shoes, run on soft and efficient surfaces, include cross-training exercises and maintain the proper running gait. Runners should also treat injuries such as sprains before running again; they should maintain optimal weight in order not to put too much strain on their joints and also stay on healthy, nutritional diets that adequately supply the essential micronutrients. |

||

| Next Article: How to Stop Arthritis |

People who are predisposed to developing osteoarthritis usually have some older members of their families who are living with the disease. Also, for those with a high hereditary risk of developing osteoarthritis, the onset of the disease is usually early.

People who are predisposed to developing osteoarthritis usually have some older members of their families who are living with the disease. Also, for those with a high hereditary risk of developing osteoarthritis, the onset of the disease is usually early. Mild to moderate osteoarthritis can be managed with

Mild to moderate osteoarthritis can be managed with  The most important consideration while running is to reduce the impact on the legs. To do this, the runner can get better running shoes which absorb most of the energy transferred to the leg from the running surface. However, another important solution is to change one’s running surface.

The most important consideration while running is to reduce the impact on the legs. To do this, the runner can get better running shoes which absorb most of the energy transferred to the leg from the running surface. However, another important solution is to change one’s running surface.