Popular Articles

- 10 Natural Sleep Supplements

- Moderex Supplement Facts

- Does Bad Sleep Damage Your Heart?

- 8 Foods That Help With Insomnia and Anxiety

- Sleeping Remedy by Natrol

- 7 Foods That Cause Insomnia

- Popular Sleep and Anxiety Drugs May Be Linked to Dementia

- Home Remedies for Sleeplessness

- Chamomile Tea for Insomnia

- Quietude Tablets [Review]

Good sleepers have 30% more of this brain chemicalIn This Article

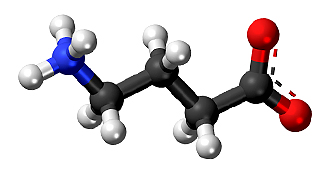

There is an amino acid that does not behave like other amino acids. Instead of using it to make proteins, the body uses this amino acid to dampen brain activity. GABA, the chief inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, is the most important amino acid to sleep, anxiety, and muscle relaxation. How much GABA is produced in your brain can determine whether you will sleep well or struggle with sleep. What is GABA? How does it promote sleep? How can you raise your brain's GABA levels? Read on to find out.

What is GABA?GABA is the acronym for gamma-aminobutyric acid. Although GABA is an amino acid, it is rarely considered as one. This is because GABA is not used to synthesize proteins in the body. Even though it is not incorporated into proteins, GABA fulfills an essential role in the body. In the central nervous system, GABA is an important neurotransmitter. It is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. Therefore, it blocks the action of excitatory brain chemicals such as glutamate and norepinephrine. Because GABA cannot pass through the blood-brain barrier, it is synthesized in the brain. GABA is produced from glutamate (the chief excitatory neurotransmitter). The inhibitory effect of GABA reduces the activities of certain brain cells. This calms down neuronal excitation. Therefore, drugs that raise the level and activity of GABA can induce sedation and relieve anxiety.

The influence of GABA has been reported in other organs of the body including the eyes, lung, liver, kidney, ovary, testis, stomach, pancreas, and respiratory tract. How GABA ActsGABA acts through GABA receptors. There are generally 2 types of GABA receptors: GABA-A and GABA-B receptors. The more important receptor, concerning sleep, is the GABA-A receptor. When GABA or an agonist binds to a GABA-A receptor, it triggers the release of chloride ions in the neuron. This causes a negative potential that inhibits the firing of new action potentials. In this way, GABA (and GABA-promoting compounds) reduce activity in brain cells with GABA-A receptors. Drugs that act at GABA-A receptors include benzodiazepines and barbiturates. Natural compounds that can activate GABA-A receptors include theanine, a compound found in green tea, and taurine, a derivative of cysteine. Low levels of GABA can interfere with slow-wave or “deep” sleep. Deep sleep is characterized by delta waves and begins 45 minutes into sleep. When it becomes difficult to reach deep sleep, the sleeper is easily aroused by distractions in his immediate environment. This is why insomniacs repeatedly wake up at night, have difficulty resuming sleep, and complain of poor-quality sleep. Because the quality of deep sleep starts to fall after the age of 10, maintaining optimal GABA levels is essential for adults suffering from insomnia. GABA Levels and SleepFor a long time, scientists have tried to determine the factors responsible for insomnia. To do this, they compare the brain activities of people suffering from insomnia to healthy people with a normal sleep-wake cycle. Recently, studies into the science of sleep yielded a breakthrough when researchers determined that the difference between those who sleep well and those who have difficulty sleeping is the neurotransmitter known as GABA. In a study published in the journal, Science Translational Medicine, researchers obtained cerebrospinal fluids from 32 insomnia patients. Cerebrospinal fluid bathes the brain and spinal cord and serves as a buffer separating the central nervous system from the rest of the body. By adding the cerebrospinal fluid samples to cells genetically engineered to produce GABA receptors (GABA-A), the researchers could determine the GABA content of the fluid through the activity triggered by the receptors. However, the insomniacs’ cerebrospinal fluids caused no spike in electrical activity in the GABA receptor cells. Thereafter, the researchers added a little GABA to the mixture. This triggered significantly electrical activity in the cells. The researchers then concluded that insomniacs have lower GABA levels than normal sleepers. A 30% DifferenceBut how big is the difference in GABA levels between good sleepers and insomniacs? A 2008 study published in the journal, Sleep, provided a good estimate of the GABA deficit of insomniacs. In that study, the researchers recruited 16 adults suffering from insomnia and another 16 good sleepers. The insomniacs already had their sleep problems for at least 10 years and were not currently on sleep medications.

The researchers, therefore, suggested that raising GABA levels in the brain should be the goal of sleep medications under development. Besides sleep, low brain GABA levels have been linked to depression, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. Studies show that people suffering from chronic insomnia have higher risks of developing psychiatric disorders. Raising GABA LevelsWhile it seems that simply taking oral GABA supplements should help raise the level of the neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, studies show that GABA does not cross the blood-brain barrier in appreciable amounts. Still, GABA supplements are commonly recommended for insomniacs in traditional medicine. Often, high doses (500 mg – 1,000 mg) of GABA are used in the hope that sufficient amounts of the amino acid will reach the brain. However, evidence suggests that high doses of GABA may trigger anxiety instead of relaxing the brain and inducing sleep. On the other hand, doctors regularly recommend drugs known to increase GABA activities or levels in the brain. While these drugs can readily cross the blood-brain barrier and bind to GABA receptors, they are often not specific in action. This means that they may bind to other receptors in the nervous system and cause serious side effects. The third option for raising GABA levels in the brain is with natural compounds that can increase GABA levels in the brain. Theanine (mentioned above) is one such phytochemical that can help raise brain GABA levels. Sedative herbs such as valerian, hops, passionflower, lemon balm, and skullcap can also increase the GABA level and/or its activity in the brain. More Studies on GABA and SleepGABA and the Sleep-Wake CycleA 1996 study published in the American Journal of Physiology provided solid evidence indicating that the release of GABA in the posterior hypothalamus increased slow-wave sleep. By using an animal model, the researchers discovered that the GABA level was selectively raised in that part of the brain during slow-wave sleep while the levels of glutamate (the major excitatory neurotransmitter) and glycine (the other main inhibitory neurotransmitter) remained unchanged. To further confirm that GABA was responsible for the deep sleep, the researchers injected a GABA-enhancing drug, muscimol, into the posterior hypothalamus. This drug binds to GABA-A receptors. After injecting it into the brain, there was an increase in slow-wave sleep. The researchers concluded that the release of GABA in the posterior hypothalamus reduced brain activity in that region and promoted deep sleep. A 2001 paper published in the journal, Trends in Neuroscience, also highlighted the importance of GABA to the sleep-wake cycle. The authors of this paper proposed a model known as the sleep switch by which the hypothalamus can control wakefulness and sleep. They confirmed the importance of the posterior hypothalamus to the sleep-wake cycle and identified a group of neurons known as orexin neurons as essential for wakefulness. Therefore, the release (and increased activity) of GABA in the posterior hypothalamus reduces the firing of the orexin neurons. This action calms down that part of the brain and promotes deep sleep. GABA and the Search for New SedativesA 2006 paper published in the journal, Sleep Medicine, showed how a better understanding of the effects of GABA on the sleep center of the brain was allowing drug researchers to design newer and better sedatives. First, the authors of the paper explained the sedative effects of benzodiazepines and drugs such as zolpidem by their ability to bind to GABA-A receptors. However, concerns about side effects from the long-term use of these drugs make finding alternative the focus of drug development in the field. The authors, therefore, proposed finding drugs that mimic GABA and those that block the removal of GABA from neurons. The authors believed the drugs that raise the level of GABA instead of binding to GABA-A receptors will be safe for long-term use in the treatment of chronic insomnia. GABA Receptors and SleepMost of the research on the link between GABA and sleep has been concentrated on the drugs that bind to GABA-A receptors. The first 3 generations of hypnotics induce sleep by targeting this receptor. However, other GABA receptors are involved in sleep. In a 2002 paper published in the journal, Neuroscience, the author discussed the role of the GABA-B receptor and a new type of GABA receptor, GABA-C, in the sleep-wake cycle. The author highlighted that the GABA-C receptor has the highest affinity for GABA. Therefore, new sedative discovery should be focused on medicinal agents that activate this receptor instead of GABA-B or GABA-A receptors. There are two obvious advantages to targeting the GABA-C receptor. First, it will require a lower dose of GABA (and, therefore, a lower dose of the GABA-promoting agent) to induce sleep. Secondly, a drug/medicinal agent that targets the GABA-C receptor is likely to produce fewer side effects compared to current sedative and hypnotic drugs. It should be noted that the GABA-C receptor is structurally related to the GABA-A receptor (in its structure, a GABA-C unit is simply a subunit of the GABA-A unit). Therefore, the current naming system identifies it not as a separate receptor family but as a subtype of the GABA-A receptor. GABA, Sleep and Mood Disorders

First, the researchers determined GABA levels in the occipital cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex of 20 adults with insomnia and 20 matched controls. The results of the study showed that the subjects with insomnia had significantly lower GABA levels in those parts of the brain compared to healthy sleepers. The researchers then reported reductions in GABA levels in the same parts of the brain in people with a major depressive disorder. This link between insomnia and mood disorder shows that a single drug or dietary supplement that raises the level of GABA in the brain will be effective in the treatment of insomnia and depression. Paradoxical GABA Response to Chronic InsomniaA 2012 study published in the journal, Sleep, found a curious effect of GABA in people with chronic insomnia. The researchers recruited 16 people with insomnia and 17 matched healthy sleepers. They asked these participants to keep sleep diaries and made sure they kept regular bedtime schedules for 9 days. Thereafter, the researchers measured the participants’ sleep-wake cycles (by polysomnography) and GABA levels (by magnetic resonance imaging). The results showed that the insomnia group reported they had fewer hours of sleep and slept poorer than the good sleepers. This finding was confirmed both by their sleep diaries and polysomnogram readings. However, the GABA levels in the occipital cortices of the insomniacs were 12% higher than the GABA levels of the healthy sleepers. This is a rather strange finding since the insomniacs did not sleep well and should, therefore, have lower GABA levels. The researchers concluded that the increased GABA levels in participants suffering from insomnia were due to an adaptive, compensatory mechanism triggered as their bodies tried to survive repeated, prolonged wakefulness (chronic hyperarousal). This form of adaption is referred to as an allostatic response and it is a survival mechanism that naturally kicks in. In this case, the brain was trying to put itself to sleep by increasing the production of GABA. Unfortunately, other mechanisms kept the insomniacs awake despite their high levels of GABA. Most likely the sensitivities of the GABA receptors were reduced and/or excitatory neurotransmitters were released in large quantities. This finding shows that while GABA is important to the sleep-wake cycle, it is not the only factor controlling sleep. Sourceshttp://www.invigorate360.com/reviews/gaba-inhbitory-neurotransmitter-that-naturally-induces-sleep/ http://www.webmd.com/sleep-disorders/news/20030912/chemical-may-link-mood-sleep-problems http://www.biophysicscenter.com/gaba-sleep-solution.html

[+] Show All

|

| Next Article: What Causes Sleep Problems |

The calming effect of GABA extends beyond the central nervous system. It is directly involved in the regulation of muscle tone. Therefore, GABA can reduce muscle spasms and provide relief for those suffering from epilepsy and restless leg syndrome.

The calming effect of GABA extends beyond the central nervous system. It is directly involved in the regulation of muscle tone. Therefore, GABA can reduce muscle spasms and provide relief for those suffering from epilepsy and restless leg syndrome. By measuring their sleep activity (with a sleep diary, actigraphy, and polysomnography) and GABA levels (through MRI or magnetic resonance imaging), the researchers determined that the average brain GABA level was 30% lower in people with insomnia compared to good sleepers.

By measuring their sleep activity (with a sleep diary, actigraphy, and polysomnography) and GABA levels (through MRI or magnetic resonance imaging), the researchers determined that the average brain GABA level was 30% lower in people with insomnia compared to good sleepers. A 2012 study published in the journal, Neuropsychopharmacology, established the comparison between low GABA levels in people suffering from insomnia and those with mood disorders.

A 2012 study published in the journal, Neuropsychopharmacology, established the comparison between low GABA levels in people suffering from insomnia and those with mood disorders.